Gōjū-Ryū Karate

History:

The origins of Gōjū-ryū (剛柔流) date back to Okinawa Island, at a time when there was only three styles of karate: Shuri-te, Tomari-te, and Naha-te. Over time, Shuri-te and Tomari-te would combine to form a single style of karate, known today as Shōrin-ryū (少林流), whereas Naha-te would go on to form the modern Gōjū-ryū style.

Naha-te was founded by Kanryō Higaonna (March 10th, 1853 – October, 1915). Originally studying Shuri-te, Higaonna ventured to Fuzhou, China, where he learnt Chinese martial arts for 13 years before returning to Okinawa in 1881. His style then became known as Naha-te.

In 1902, Higaonna began teaching Chōjun Miyagi (April 25th, 1888 – October 8th, 1953), who was 14 at the time. Miyagi studied Naha-te as Higaonna’s top student until his master’s death in 1915.

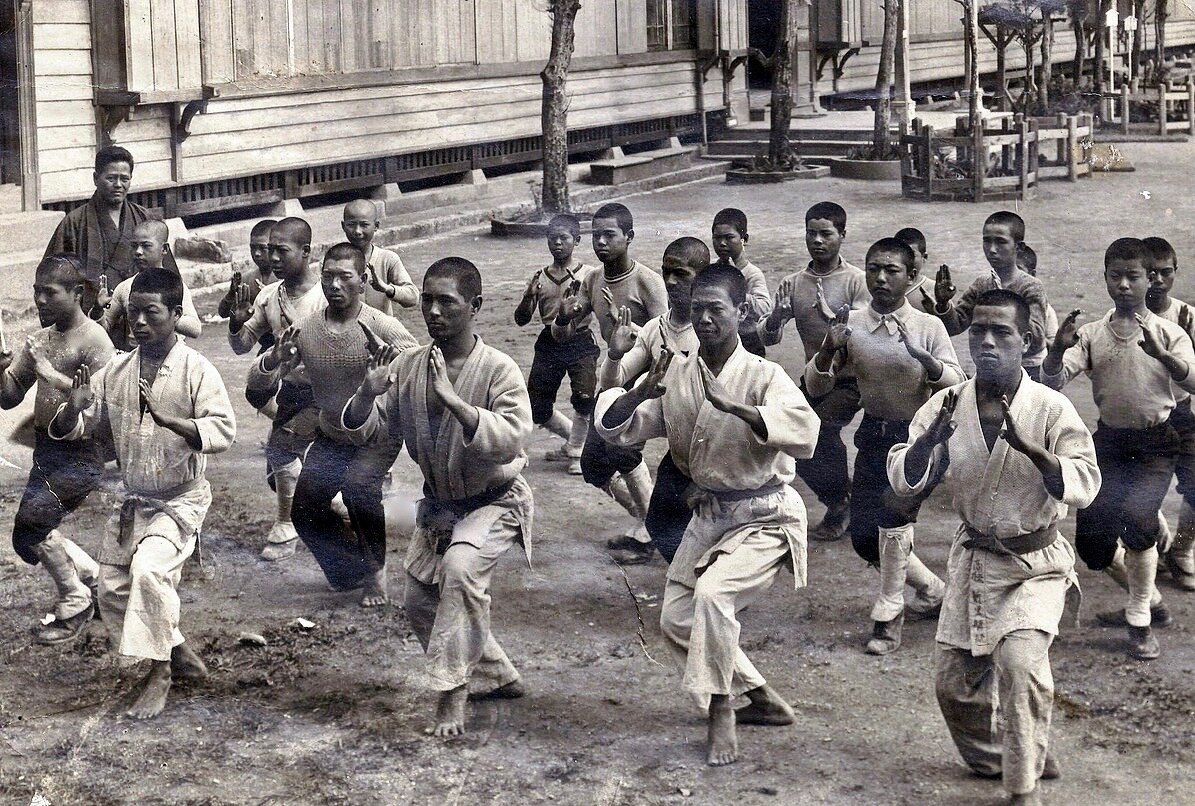

Miyagi continued to teach Higaonna’s Naha-te throughout Okinawa and mainland Japan, visiting China to train as his master once had. He eventually structured the style into a discipline which was easier to teach.

In 1930, Miyagi’s top disciple at the time, Jin’an Shinzato (February 5th, 1901 – March 31st, 1945), attended the All Japan Martial Arts Meet in Tokyo on behalf of his master. Here, he was asked for the name of the style he practiced; however, Miyagi had not yet named it, as schools and styles did not exist in Okinawan karate. Instead, Shinzato improvised the name Hankō-ryū (半硬流), meaning “half-hard style”.

Upon return to Okinawa, Shinzato discussed the incident with Miyagi, who decided on the name Gōjū-ryū. The inspiration for this name comes from the third line of the "Eight Important Precepts of Kempo” (拳法之大要八句= Kenpo no taiyoku hakku): a poem from The Bubishi (a comprehensive ancient Chinese martial arts manual). The line states: “Ho wa goju wo tondo su”, meaning “The way of inhaling and exhaling is both hard and soft”. Thus, Gōjū-ryū means “hard-soft style”. Gō, which means “hard”, refers to closed hand techniques or straight linear attacks, and Jū, which means “soft”, refers to open hand techniques and circular movements.

In his 40s and 50s, Miyagi worked hard to promote Gōjū-ryū throughout mainland Japan, and in Hawaii. His efforts to spread Gōjū-ryū were so successful that, in 1937, the Dai Nippon Butokukai recognised his style as an official martial art, and he as its official master, honouring him with the Kyoshi title. Finally, in 1998, the Nippon Kobudo Kyokai (Japan Traditional Martial Arts Association) recognised Gōjū-ryū as an ancient form of traditional martial art.

Chōjun Miyagi passed away on October 8, 1953, at the age of 65. His noteworthy students include Jin'an Shinzato, Meitoku Yagi, Seiko Higa, Seikichi Toguchi, and Ei'ichi Miyazato - the founder of the Jundokan (see the Jundokan So-Honbu page).

Miyagi believed that the ultimate aim of karate was to build one’s character, conquer human misery, and to find spiritual freedom.

He is noted for having said: “人に打たれず、人を打たず、事なきを基とするなり” , which means: “Hit not. Be not hit. Avoiding conflict is the fundamental principle”.

Kata:

Gōjū-ryū has 12 core kata which are the essence and foundation of all training. Kata are the prescribed forms or patterns that we learn and practice step by step, and later analyse the techniques for practical defence.

The kata of Gōjū-ryū can be categorised into one of three headings:

Kihongata (“basic kata”):

Sanchin 三戦 (“three battles”)

Kaishu-gata (“open-hand kata”):

Gekisai-ichi / Gekisai-ni 撃砕一 / 撃砕二 (“attack and destroy”)

Saifa 砕破 (“smash and tear”)

Seiyunchin 制引戦 (“control and pull into battle”)

Shisochin 四向戦 (“fight in four directions”)

Sanseiru 三十六手 (“36 hands”)

Seipai 十八手 (“18 hands”)

Kururunfa 久留頓破 (“holding on long and suddenly striking”)

Seisan 十三手 (“13 hands”)

Suparinpei 壱百零八 (“108 hands”)

Heishu-gata (“close-hand kata”):

Tensho 転掌 (“revolving palms”)

The foundation of all kata is Sanchin: a breathing kata which aims to unify the mind, body and spirit. Sanchin is performed slowly with tension to develop movement, breathing, stance and posture, internal strength, and stability of both the mind and body. Similarly, Tensho combines dynamic breathing with soft, flowing hand movements. Both Sanchin and Tensho kata contain distinctly different breathing patterns, and are thus considered to be the essence of the “gō” (hard) and “jū” (soft) of Gōjū-ryū.

The majority of the kata practiced in Gōjū-ryū today were brought back from China by Kanryō Higaonna. This includes Sanchin kata, which was originally preformed with open hands but was later changed to closed hands by Higaonna.

Chōjun Miyagi developed Tensho kata in 1921 to further complete his style. He also developed the Gekisai kata in 1940 as a simple form of physical exercise for high school students, and to help popularise Gōjū-ryū throughout Okinawa.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

Some Goju-ryu dojos only categorise kata as being either ‘heishugata’ (close hand) or ‘kaishukata’ (open hand), in which Sanchin kata is considered to be heishugata. The Jundokan Dojo, however, categorises them into 3 sections, whereby Sanchin is the ‘kihongata’ (basic kata). This can be seen in the picture above showing the kata names and categories hand written by Ei’ichi Miyazato-Sensei.

One important question that is often unaddressed is: why is Tensho kata categorised as heishugata (close hand) when most of the techniques are, in fact, open handed?

The answer lies not in the hand movements of the kata itself, but rather in the way it is preformed and the direction of energy. In kaishugata, where the hands are open, the energy flowing through the body is directed out of the open hands (and into your opponent). These kata as thus ‘external’ in their purpose.

However, with heishugata, where the hands are closed, the energy is directed back into the body where it is internalised. Thus, the ‘close’ here refers to the continuous tension of the body (like in Sanchin, hence why it too is sometimes referred to as heishugata).

In short, the heishugata are named as such because of (a) the internal flow of energy created, and (b) the continuous tension in the body, not because the hand movements are preformed with closed hands.